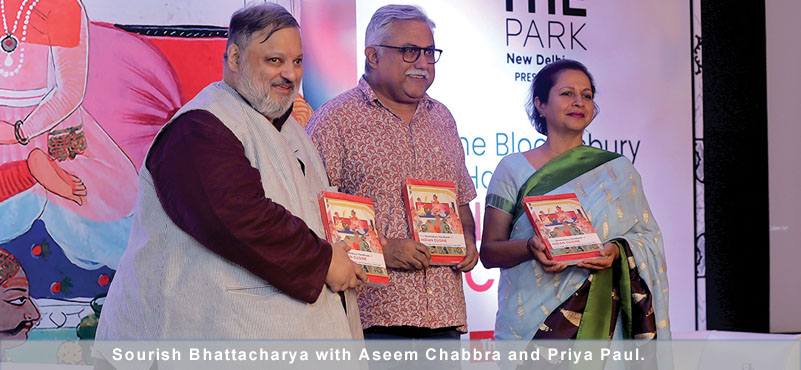

Bloomsbury has published this important milestone book of Indian cuisine, edited by Colleen Taylor Sen, Sourish Bhattacharya and Helen Saberi. At its launch at The Park in New Delhi, food enthusiasts got together to hear a conversation around the book, with the authors sharing their perspective. Participants included Priya Paul, chairperson, The Park Hotels; Sourish Bhattacharya, columnist and food writer; anchor for the evening, Aseem Chabbra, author and commentator and a host of contributors who could attend the event.

Aseem ChabbrA: The book is such a treasure trove of information about food. It’s something that you will dip into again and again, whether it is recipes on how to make certain dishes or history of some restaurants or history of India as such, with invaders and other things and foods, they brought, iconic restaurants, iconic hotels. It’s just so, so fascinating. So, just give us a sense of how does a book like this get put together?

Sourish: Colleen is here. And Pawan Agarwal is right here. He was then the FSSAI CEO. He is responsible for getting Colleen and me together. I had just read Colleen, I had not known her personally, but it was Mr. Agarwal who first connected us.

Colleen: This book goes back 15 years when we had a proposal to Oxford University Press for a similar book. Well, what happened is we went through all the rigmarole, and it went all the way up. And then at the last minute, when the contract was ready, Oxford cancelled it. They cancelled their entire food series, not just this book. So when, Sourish approached me, I said, we already have kind of a proposal in place, so let us start with that.

But the difference is that 15 years ago, there weren’t that many really excellent writers about Indian food that you have now. So, this time we were able to draw upon this wonderful pool of expertise, these great writers that both Sourish and I knew, and I think that’s what really made the book a success.

Sourish: We have truly a range of contributors. We have the youngest who’s sitting right in front. He’s now 18 years old. Wow. He wrote the Tamil section. His father is Tamil and his father is now happy to promote vegan cuisine which unfortunately we did not touch a lot on in the book. And then we have people like Priya Mani, who is a well-known writer who wrote the Rites of Passage section.

Aseem: If you can give us some more details about the thought that went into the cities you selected, the restaurant that you wanted to touch upon.

Aseem: If you can give us some more details about the thought that went into the cities you selected, the restaurant that you wanted to touch upon.

Sourish: What Colleen mentions in her introduction, I think makes a lot of sense. She says that this is the history, geography, and the present of Indian cuisine. You know, people like Priya Paul and her magnificent bank of Chefs, were defining modern Indian cuisine as we know it now. Actually, there is so much to write about India.

Colleen: We wanted to make sure we covered all the Indian states, because that’s something that hadn’t been done. And we wanted to do as many cities as possible. But in the sense, we were partly constrained by the availability of who could write about these things. We didn’t just want any odd person write about something they didn’t know. So, we really relied a lot on the expertise of the writers. Now I know there’s things we left out and there are other things we could cover, but I think the book is a good mix of kind of factual information and really profiles of some interesting personalities. So, I think we tried to get a balance between really encyclopedia facts and human-interest stories. And I hope we succeeded.

Aseem: More than succeeded. I mentioned Iranian restaurant. Did anyone here ever think about the fact that why in Bombay – all the Iranian restaurants are always at the corner of the street? It is mentioned in the book that apparently it was considered bad luck among Hindu restaurant owners and probably other religions.

Sourish: What they call the gomukh plot of land. Even in Delhi, you know it is considered not an suspicious location to have, you know, so the Iranis did not believe in all this, so they happily took over these corners and they thrived after that. It is of course a lot more noticeable.

Aseem: Tell me about the cities that you cover and the range of them. I mean Lucknow, Varanasi and the bigger cities. Tell me how you went about that?

Sourish: Between Colleen and I, we did a lot thinking about that. You know, because we did, for instance, Banaras. But why do we leave something else, say Rampur. We did Hyderabad but why did we leave something in Kerala? We were bound by the number of words, so we went for the most important cities from a food perspective.

Colleen: Well, the interesting thing was that the one we almost neglected, the last one we did, the last entry was Calcutta. And for some reason, I don’t know what happened. We asked people, and it, it just didn’t happen. I thought, oh my God, you know, two people; one Bengali and one semi-Bengali. And I think that was the last entry we actually wrote for the book.

Sourish: Why not bring in our youngest contributor here and see the writing from his perspective and the whole experience?

The Tamil Cuisine Section

SURYA VIR VAIDYANATHAN: It was really an amazing opportunity for me. I was able to connect with my Tamil heritage and culture in more nuance and different perspective.

For me, I wrote a lot about my understanding and my culture and heritage, which was through my grandmother from Chennai. She cooked us vegetarian Tamil Iyer food every single day. So, a lot of those recipes I cooked with her when I was in Chennai doing research for the book. I was there for a month cooking the recipes every single day and trying to understand how it was made. So, I have featured many of those household recipes in the book. Apart from that, I was able to learn from my aunt and her as well, the historical significance of what I was eating. A big part of our community, the Iyer community, is to be sustainable since the Vedic period. So that was a big part of our culture till day. About Tamil Nadu I have been able to learn how many different communities there really are. And I did lot of research about Biryani. Because there were so many different types of communities, each with different ingredients and historical experiences, perspectives and livelihoods. So, it was very interesting to see Tamil Nadu as a more of a symbiotic stage.

Alcohol Matters

Prasun Chatterjee: You know, there’s always this sort of criticism of historians that they do not often connect from their academic world to a wider leadership. So, this was my opportunity to write in that manner. I had an article on alcohol which was an academic essay. But this was the opportunity to make it wider, connect with everyone.

So I had earlier specialized on 17th century, and when I started looking into the early Indian past, when I started looking at the colonial Raj era, I found that a lot of writing about alcohol either went towards fact finding, or it went towards, the modern Indian debates about prohibition and other things. But no one really thought about the experiences, the stories we have across sources, across literature and how to really treat them. So, if you see my essay, my engagement was to actually look at the sources, as historians say, and what kind of questions we can ask of that. Not everything is linear, in early times in India, there was a sort of a scepticism about drinking alcohol or now it’s very liberal.

So I had earlier specialized on 17th century, and when I started looking into the early Indian past, when I started looking at the colonial Raj era, I found that a lot of writing about alcohol either went towards fact finding, or it went towards, the modern Indian debates about prohibition and other things. But no one really thought about the experiences, the stories we have across sources, across literature and how to really treat them. So, if you see my essay, my engagement was to actually look at the sources, as historians say, and what kind of questions we can ask of that. Not everything is linear, in early times in India, there was a sort of a scepticism about drinking alcohol or now it’s very liberal.

It’s not like that. There are ambivalences in attitudes all the time in our societies and in our cultures, in our communities. So, when we look at the sources, we find these ambivalences, you’ll find ambivalences in attitudes. On the one hand, you would see Zia Uddin Berdani who is advising the Sultan of Delhi as to how to rule. And Islam really does not prescribe the drinking of alcohol. But on the other hand, he advises the Sultan that he shouldn’t drink too much because that’s likely to create problems in his ranks. But on the other hand, if he on the battlefield does not create those opportunities for his soldiers to have a little bit of fun, then there could be a rebellion.

Sourish: We Bengalis have grown up, uh, listening to the chat part. And there is a great description of Ma Durga being offered alcohol by Lord Shiva, and she has that alcohol and she’s in a such a state of frenzy that she would just kill every Asura that comes in a way.

Aseem: So, there is this indication towards power violence, forcing something, through the use of alcohol. But on the other hand, there are stories which indicate towards the pleasure, the kind of atmosphere that is created, in our community while drinking alcohol. So, these ambivalences, these ways of looking at our sources also tell us that when we encounter something from the 5th century or 13th century, we should not take it at face value. We should, we should look at what it means, why the writer says certain things in a certain context. And that is perhaps not exactly how it is today. So often we make the mistake of quoting something from an earlier time and thinking that that’s exactly how it is today.

There are references to wine. You talk about Dutch and the KamaSutra courts where wine keeps reoccurring as an alcohol choice. And yet in the modern India that we know, it’s only in the upper class now, that go to five-star hotels or restaurants that order. And it’s the perception that Punjabis prefer whiskey. So, tell us about why wine didn’t pick up really that well, as Scotch Whiskey did.

Sourish: There is a lovely description of Thomas Rose. You know, when he met Jehangir when he came as ambassador of the East India company, he was not being given access to Jehangir. So, then he had carried with him wine from Britain and offered it to him and woed him and got him to sign his papers for the Surat factory and that was the beginning of the British Raj.

The Book and Hospitality Business

Aseem: There was always a culture of imported wine. You’re in the hospitality business, right? More Indians in your hotel ask for whiskey, right? Than wine.

Priya Paul: I feel that the younger generation is a mix of white alcohol of course. Wine is a great fast going category. And because we’re now producing so much, at different price change. Indian wines are also being consumed now and a small fraction of imported wines.

Aseem: Being in the hospitality business… when you have students to come and join your hotel management programme in Mumbai, where do you see this book fit it?

Priya Paul: We have that in Navi Mumbai. But apart from the hospitality students, I think for all professionals, there’s so much to learn from this book. Professionals, foodies, people who are interested. I have just delved little bits and pieces. So, it really takes off from Dr. Chaya’s book and it is updated. It’s an amalgamation of beautiful writing from top people who are experts on their cultures and on the cuisine. And, of course, the historical restaurants that have been at the forefront in India.

Sourish: I always wanted to ask you this question, but when did Flurry come into the Park Hotel bouquet?

Priya Paul: Flurry’s was started 1927 by Mr. & Mrs. Flurry’s. And I think the rumour and gossip is that they were about to retire and wanted to leave India in the early sixties, I would say 1963. And I think the rumour is that they were walking on Park Street and so was my uncle Jit Paul, and they struck a deal on the street. Their factory was right behind what is now the Park Hotel. And The Park was under construction at that time. It has always been there.

Rice matters

TANUSHREE: I contributed three chapters – West Bengal, Assam and Rice.

I will talk a bit about rice because both Assam and West Bengal will feature when we talk about rice. The rice chapter is based on about six years of my research on rice. I am a development worker by professional. So, as I travel across India, I come across a lot of farmers, rice farmers, indirectly, indirectly.

And we’re a heavily rice eating country, like 60% of the population eats rice. And I am a Bengali from Assam. West Bengal is the largest producer of rice in our country. Interestingly when we look at rice. And that’s what struck me is that, you know, Southeast Asia documents its rice history so beautifully. You find so much document about rice in Southeast Asia. There’s hardly anything written about rice in India, especially about the antiquity of rice. And that’s how I started my food research. Otherwise, I dwell on Vedic to mediaeval Indian food. And there’s so much reference embedded in this text about rice. And that’s where I started looking at antiquity of rice in our Vedic text. And it’s very interesting now because it’s like the past three or four years when we are at a place when our archaeologists are coming to this realization that rice cultivation in India, in fact, multi cropping of rice in India is probably the first multi cropping in the world.

And we’re a heavily rice eating country, like 60% of the population eats rice. And I am a Bengali from Assam. West Bengal is the largest producer of rice in our country. Interestingly when we look at rice. And that’s what struck me is that, you know, Southeast Asia documents its rice history so beautifully. You find so much document about rice in Southeast Asia. There’s hardly anything written about rice in India, especially about the antiquity of rice. And that’s how I started my food research. Otherwise, I dwell on Vedic to mediaeval Indian food. And there’s so much reference embedded in this text about rice. And that’s where I started looking at antiquity of rice in our Vedic text. And it’s very interesting now because it’s like the past three or four years when we are at a place when our archaeologists are coming to this realization that rice cultivation in India, in fact, multi cropping of rice in India is probably the first multi cropping in the world.

The archaeological sites up in U.P are the first to examples of multi cropping of rice, wheat, millet, sesame, all of them together. So, it was an interesting journey to just distil all of that. And I’ll just share with you a bit of trivia which features in the book. And I find it interesting that a lot of the varieties that are mentioned in these texts pretty early on, starting from the Atharva Ved when we first find the mention of rice, I mean, growing of rice in India is from 6,000 BC. That’s when rice was being grown. Cultivation of rice is from 2000 BC. We are a pretty old rice growing culture. But the first mention of rice comes in the Atharva Ved as Vrihi which is the Sanskrit word for rice. By 900 – 800BC is when rice prominently starts featuring. But how important rice is to us culturally, I think nothing says that better than the first Sutra of Mahayama Buddhism in India, called the Shali stupa sutra translated, it means a stock of paddy. That is how significant it is to us culturally and for our ritualistic and religious matters. In fact, I think most of the major classification of rice, we come to it by the time we come to the Arthashatra we find the mention of black rice, basmati and red rice and Navara which is the oldest wild rice variety, which is still being consumed. In fact for my research, I work with a very traditional healer from Tamil Nadu and they still prescribe navara for healing purposes, especially to women through their various stages in life.

Diaspora

Aseem: Colleen, I remember there was in NY a little hole in the wall restaurant, you know, you could barely even notice it. And there was this African American woman who was, you know, quite old even at that point of, I don’t know if she’s still alive or not, we used to run the place, but she used to make the best Paranthas.

You couldn’t eat there. It was too dark. And one time I asked her, I said, how’d you learn this? And she pointed to a photograph of a man on the wall. Looked like a general or something like that. With a moustache. He was a Bangladeshi and she was actually married to him. And it is very interesting how food passed on.

COLLEEN: Yeah, that’s very true. There was certainly a lot of Bengali settlers who, they were based actually in New Orleans, and gradually they went north and there was another group of Bengalis who jumped ship and then were in New York. They couldn’t bring their wives over. So, they married African-American and Puerto Rican women. And even when I was at Columbia University, oh my God, this was in like the late sixties. There was still a few of these little restaurants around Harlem, which was near Columbia that were run by these people. But they have all pretty much closed down now. But they were really pretty good. I mean, they were a little bit more authentic than some of the restaurants that we have.

COLLEEN: Yeah, that’s very true. There was certainly a lot of Bengali settlers who, they were based actually in New Orleans, and gradually they went north and there was another group of Bengalis who jumped ship and then were in New York. They couldn’t bring their wives over. So, they married African-American and Puerto Rican women. And even when I was at Columbia University, oh my God, this was in like the late sixties. There was still a few of these little restaurants around Harlem, which was near Columbia that were run by these people. But they have all pretty much closed down now. But they were really pretty good. I mean, they were a little bit more authentic than some of the restaurants that we have.

Aseem: The other story of the diaspora, is there was Sikhs who came from I guess Canada, many of them and sort of crossed over into, from Vancouver across into California, through Washington, Oregon State because, and California has that very agricultural land. You know, in the early 1990s and for quite a while, the laws did not allow immigrants who would arrive to bring their own wives as such. So many of them married Mexican women. So, not only did they had children who were half Sikh and half Mexican, but again, the food was mixed and emerged and evolved as such. It was really interesting.

Colleen: Yeah, absolutely, and really there is so many convergences between Mexican and Indian food. And in fact, here in Chicago some of the Indian restaurants actually have Mexican cooks. And I don’t think it’s that hard for them to do real Indian food. There’s a lot of similarities though.

Priya Paul: One of the reasons I am passionately interested in this book is, is to really look at ingredients across India, the forgotten ones, the ones you see in somewhere in the Nilgiris and you don’t see anywhere else in the country. How do we share that knowledge and how do we share this with everybody? And the rice stories are beautiful. And now of course we are going through the year of the millets.