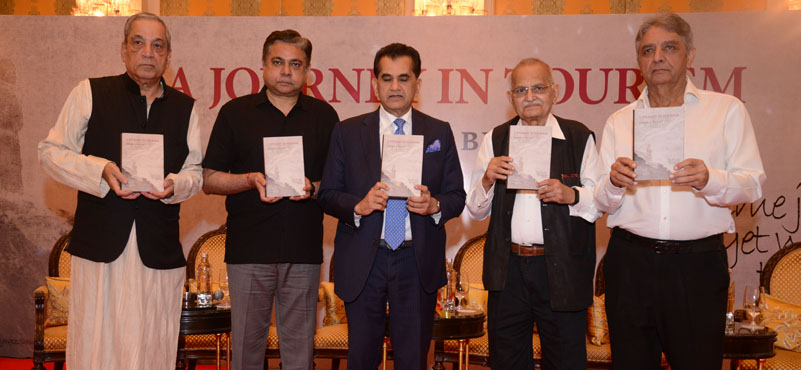

What’s the road ahead for Indian Tourism? At an event to launch a book, “A Journey in Tourism”, by editor Navin Berry, compiling his experiences and learnings form being 50 years in this industry, a high-powered panel discussion featured Amitabh Kant, G20 Sherpa; Patu Keswani, CMD, Lemon Tree Hotels; Rajeev Sethi, art and culture thespian; Aman Nath, hotelier and historian; Iqbal Chand Malhotra, author and film maker; the discussion was moderated by Barkha Dutt, TV anchor and journalist. The book was formally released by Amitabh Kant; SK Misra, chairman, IRTHD and former vice chairman INTACH; Vinod Kumar Duggal, former Governor; and Arvind Singh, former secretary tourism, GOI.

Barkha Dutt: I grew up in a home where how to make India’s tourism story better was a dining table conversation because my father was also in the tourism industry and many of you knew him. Whether you look at aviation or you look at hotels or you look at amenities, there’s an interconnectedness at the heart of it. And before I actually come to Navin to talk a little bit about his book, Aman, you wanted to talk about the interconnectedness and the joining of the dots. So, let’s start with you. Let’s start with each of you giving one takeaway that you had from reading the book and I’ll give the last comment then to Mr. Berry. Go ahead, Aman.

Barkha Dutt: I grew up in a home where how to make India’s tourism story better was a dining table conversation because my father was also in the tourism industry and many of you knew him. Whether you look at aviation or you look at hotels or you look at amenities, there’s an interconnectedness at the heart of it. And before I actually come to Navin to talk a little bit about his book, Aman, you wanted to talk about the interconnectedness and the joining of the dots. So, let’s start with you. Let’s start with each of you giving one takeaway that you had from reading the book and I’ll give the last comment then to Mr. Berry. Go ahead, Aman.

Aman Nath: Navin said that I should look at a particular section where he talks about connecting the dots. So, I think that the tourism industry is an elephant, really a lumbering elephant. And there’s nobody to blame because how do you connect an elephant which is with all the legs walking in different directions. So, if I was to do this book, if it was not an art autobiography, I would’ve called the book ‘Ankush’; ‘Ankush’ being the goad which pokes the elephant and tells him to move. So, I think you’ve been that goad because you’ve been trying very hard to connect the dots because there are so many ministries.

Barkha Dutt: But what’s stopping the elephant from moving?

Aman Nath: The system.

Barkha Dutt: No, I’m actually asking a serious question. If you had to sort of say this is the elephant and this is why it needs to move, it needs to move, but it’s kind of stuck.

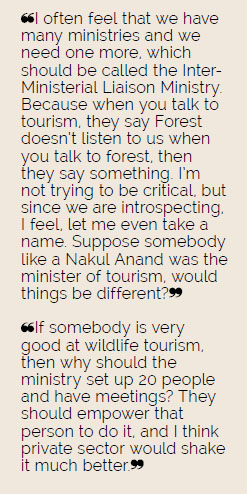

Aman Nath: To move because the ministries can’t move by themselves. I often feel that we have many ministries and we need one more, which should be called the Inter-Ministerial Liaison Ministry. Because when you talk to tourism, they say Forest doesn’t listen to us when you talk to forest, then they say something. So, if they are not able to coordinate and they need a Navin Berry to kind of put them on a forum to go through the whole exercise of assembling them, I have seen you do it for years. So, I mean this is a kind of in-house thing. I’m not trying to be critical, but since we are introspecting, I feel, let me even take a name. Suppose somebody like a Nakul Anand was the minister of tourism, would things be different?

Barkha Dutt: So, are you suggesting that if someone from the trade was in government it would be different?

Aman Nath: I think so. Somebody who’s established themselves, because you would never have a situation that you’ve got funds and they lapse because you don’t know what to do because you know the players. If somebody is very good at wildlife tourism, then why should the ministry set up 20 people and have meetings? They should empower that person to do it, and I think private sector would shake it much better.

Barkha Dutt: Okay, let’s take that thought to you Iqbal. Is that what you would pick up that when you were going through Navin’s book, what stayed with you? What did you agree with, what did you disagree with?

Iqbal Chand Malhotra: Well, when I got Navin’s book last evening. So, I spent quite a bit of time going through it, and then I went to my computer and I switched on Wikipedia and I saw some interesting figures. Foreign tourist arrivals in 1997 were 2.37 million. And in 2022, in 25 years, they’d just gone up to 6.19 million. Of course, there was a spike about 10 million and there was a pandemic, but it came down to 6.19 and earnings from foreign tourism in 1997 were $2.9 billion and in 2020 there were just $6.9 billion. Now, I’ve always wondered how countries like Egypt, Greece, and Peru have been so successful in marketing their ruins and making billions of dollars out of them. And how countries like Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Namibia, Botswana, you name it, have been successful in marketing their wildlife and made millions out of it.

So, I just figured that there must be some reason, and I looked at three factors that struck me. My exposure to tourism is because my wife and I have produced about 6 travel shows over the last 25 years. We haven’t done one for the last 10 years. And I came out with three factors. The first was price, and I found that you find that India is not a price competitive market because the burden of indirect taxation, which is levied on the poor tourist is very unattractive for him. And if you look at countries like Sri Lanka and then you look at Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, you’ve got much better options at much lower prices. The second thing I noticed was infrastructure. Now infrastructure is necessary to provide accessibility. So, if you look at, say for example wildlife in Africa, you’ve got all these plethora of small charter companies, air charter companies that have these single engines and two engine turboprops and they can fly you anywhere and within Africa, across borders.

So why hasn’t that air charter industry been established in India to link up all the wildlife sites and all the forts because that’s again a great thematic subject and of interest as we come back to the lack of our ability to market our ruins.

And the third thing is the experience of the traveler who comes to India and does he want to come back and does he want to be preached at, we have moral police in operation. Do people want to be judged when they come here on what they’re doing and how they’re behaving?

There used to be a lot of tourists in Goa at one time 30 years ago, foreign tourists. And if I remember about 50 years ago we had a family guru called Baba Neem Caroli, and in his ashram I have seen Steve Jobs and Richard Alpert. Richard Alpert was the guy who founded or discovered LSD and Steve Jobs is the founder of Apple. Now these are icons and for some reason nobody in India thought of using them to endorse India as a great destination for spiritual tourism as against religious tourism, but spiritual tourism. So, there are many issues over here and nobody has looked at it holistically and try to figure out that do what we really want to do, we do something about it, or do we just want to say it is ok as is.

Barkha Dutt: So, let me flip it around and take that to Mr. Keswani because actually when those of us who travel outside India, one of the things, if you’re not talking about the East, you mentioned a lot of the countries in the East or Sri Lanka, but if you go to the west, the hotels are crappy, right? And you’re paying a lot for really poor service. And I mean most of us would’ve at some point said, oh my God, our service industry is so much better. Indian hotels by and large really, really are exceptional. Why then or what then is the problem?

Rural Tourism is the Next Sunrise Industry!

SK Misra, chairman, Indian Trust for Rural Heritage and Development

Aman Nath mentioned France as a number of tourists they’re getting and number of tourists we are getting, we do respect you. I do not agree with you. You cannot compare France. What are the number of days that the tourist spends in France? Compare it to India, multiply that, and then you get the real figures. Apart from that, I entirely agree with Amitabh that mass tourism would destroy the country. Imagine 30-40 million people descending on the country. It doesn’t make sense. It has to be selective.

Firstly, what is the objective of tourism? The objective so far as India is concerned should be to improve the lives of millions of people, to have a direct impact on them. In a very small way, when I secretary, I started the Surajkund Mela. The purpose behind it was that our crafts were one of the major attractions, but craftsmen had been neglected earlier. So, we said tourism should act as a patron of the crafts. And we got master craftsmen from all over the country. Now more than 35 years have passed and it continues to be a big success.

So, I think what we need to do is now we have to move to new areas. I remember in the seventies, I had said, domestic tourism is a bedrock of Indian tourism. You must promote domestic tourism and not just be concerned with foreign exchange earnings. Now domestic tourism has caught on; our next step should be to ensure that very direct impact on the people, which will come from rural tourism.

In promoting rural we will be achieving the vision of Mahatma Gandhi. Rural sector will benefit tourism and a large number of tourists who come to India are interested in seeing the real India, not move from one five-star hotel to another, and then you can link the two – they stay in an urban centres like Agra or Banaras or something and then taken into the interior.

Patu Keswani: I think, well, I have not come here as a hotelier. So, I’m going to go off your question. See, I loved your book. Thank you Navin for sending it to me yesterday and I read it today, and I think it’s very well written, very topical, and in fact, I’ve been talking to the Secretary, she had called me a couple of times about how we should change tourism just in the last three weeks. And it’s a very simple thing. When do things work and when do they not work? If there are 50 voices and we are a democracy and we are proud of it, but there is no alignment, then nothing will work. Each individual stakeholder will do what is best for him or herself. I think a very fundamental issue in our country is that we talk about where we want to go, but nobody asks how we’re going to execute it and therefore your recommendation that there should be a nodal agency if you are really interested in getting it to work, it needs two things.

The problem is tourism is a state subject. It must be in the concurrent list, number one, which means the centre has some say. Number two, there should be a leader like you recommended who has the power to get things done, obviously with vision, and you can define that vision, that could be a democratic decision. Take the inputs of a hundred stakeholders, but one person to execute. My view is simply that, and what I have been putting forward through the Hotel Association and to various government officials, is whether tourism is a business that could transform our demographic dividend. It has to be seen as a political economic decision, not as an economic decision because it could easily absorb the 10 to 15 million guys who need a job every year. We could absorb half of them for the next 10 years. It could change India’s, it could improve India’s demographic dividends.

So therefore, rather than talk about hotels, which is one subset or X, Y, Z, see we are all visitors here. We are all tourists. I like what you said, visitor economy. Each and every one of us is a visitor somewhere. That’s the human condition. So, it’s overarching. I wouldn’t talk about this aspect of that. I would say somebody has to take a call and it’s the Prime Minister, by the way, who has to say, I’m going to give a part of my political capital. I am going to set up this agency, whether it’s in the PMO, that is with a structure with his political heft and sure transformation. What has happened with, look, at the National Highways? Is not that led as a mission. It’s insane what they’ve done. Even airports, it’s all been unleashed. See, entrepreneurial energy will come, but somebody has to channel it. So that’s my only comment that it’s a beautiful book. I hope Mr. Modi reads it and gets inspired by it because it’s certainly inspired me.

Barkha Dutt: Yeah, that’s a great point actually about the analogy, Rajeev with the highways, that when you put your mind to something, the infrastructure story of India has been pretty great when you look at it in terms of the state of airports, the state of roads, and if you actually think of it as something that benefits the political economy, creates jobs, not just as a niche area that you’re having a tourism discussion. Rajeev, you’ve been in one way or the other in the space of branding India to the world with arts, with textiles, with so much of our sort of heritage as it were. What’s holding us back?

Rajeev Sethi: Great. I see so many friends and as long as I remember Navin, but my five points of intervention would be very brief and I made them briefer. But we’ve discussed this over so many decades. I recall meeting my friend Navin in the seventies of the last century, and we would often travel on a bus to and fro from Chandigarh. His Destination India magazine – was his passionate article of faith and the sheer invention of tourism in the early sort, newly created state of Haryana was one of his very consistent beats. And I recall Chappy Misra (SK Misra) was central to both of us as young men. And Navin got to write plenty about the many birds perched on state highways as tourist complexes out of creating the highways in fact, but also going into pug dundees, which bought out things from the villages, bought out places which nobody would have gone to, they didn’t know they existed.

Roads went to that area principally because of what Chappy had in mind to create that network. And then my plans of course were different. I wasn’t talking about the tourist complex, although assigned to one to work with, when I finished, was this plan on a rural hub created by villagers themselves, but it never took off.

There was a whole issue of orientation of local people as guides of oral histories connecting the tangible with the intangible resonances. There was an interfacing of traditional knowledge systems with evolving technologies, indigenous like beauty clinics and villages created for small towns and ‘basties’ as part of health tourism, but never really a curtises as health tourism. But creating an annual collection of best souvenirs, our takeaways, a mapping of skilled craftspeople. It’s conversion to utilitarian objects offered a huge imaginative canvas. We could have mobile kiosk retails and haats near tourist spots, but nothing really happened. And that is a problem. We made the present highway minister a presentation. We made an appeal to the minister saying that, which you mentioned again, again that connecting arts and crafts to infrastructure would be the next thing. It just can’t be left to emporiums and museums.

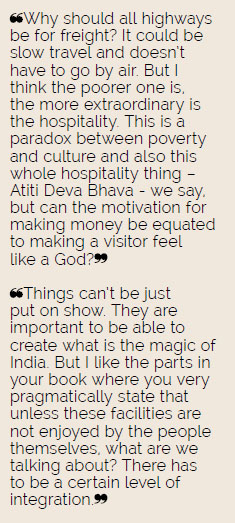

It has to go into rest houses, it has to go into villages, it has to go to where people go. And why should all highways be for freight? It could be slow travel and doesn’t have to go by air. But I think the poorer one is, the more extraordinary is the hospitality. This is a paradox between poverty and culture and also this whole hospitality thing – Atiti Deva Bhava – we say, but can the motivation for making money be equated to making a visitor feel like a God?

I’m just sharing some key takeaways from his book. The first, which he extols fairly powerfully, is the idea that tourism is everybody’s business. It’s everybody’s business. It’s yours and mine. It is, of course the tourist, but is also the ‘shakara wallas’, the coconut cellars and somehow, it’s been seen in isolation as part of a very exclusive club. It has to move out of that exclusive club, out of that ‘suit boot’ positioning into every man’s product, both as a consumer as well as someone who benefits from it.

The corollary that comes from it, and I think Navin mentions it, is the fact that the ministry of tourism, as an enabler, doesn’t have the teeth to actually do very much more than state a position and that lack of consistency that he talks about. But tourism is everybody else’s business. Every other ministry’s business. All the elements that go into serving the civic amenities for you and me as people, as citizens of the country, if that product meets our requirements, it meets the requirements of the tourists.

That, again, is a very important takeaway in terms of how to look at and understand the tourism product. These civic amenities include everything from better cities, cleanliness, hygiene, safety, security, transportation, signages, electricity, toilets, drinking water, food, food stalls, friendly police. If we have that for the citizens of our country, the tourism product is automatically enabled.

What he’s also talking about is the very nature of the travel economy and the possibility of a national tourism mission. The fact of certain redundancies in terms of the industry associations, because their sheer limitation in terms of the roles that they play, when in fact tourism should represent a much larger body of people.

Now the greatest luxury has no price tag attached to it and we know this and have experienced it. I know I’m being totally idealistic. I’m nothing else all these 70 years, but how to make a business out of something that is best offered free is the dichotomy. And I still don’t know that hospitality when it gets converted to a business, which most of, I’ve been talking to Navin known often that all the gatherings always hoteliers and people in the trade. But really when we talk of Atiti Deva Bhava then it’s everyone. So there are many, many issues that come on the way when we get to the pug dundee and we get off the highway and these have been taken up over the last 60 years. I know Navin has mentioned them in the book here and there, but I do not know why it doesn’t really start showing some concrete results.

Barkha Dutt: Thank you, Rajeev. Thank you for that. Navin Berry, I think we must bring you into the conversation with this book. Obviously, you’ve had a ringside view of what’s been happening in this space for so many years. The one thing that everybody seems to agree on is a kind of holistic approach. There’ve been many ideas from this stage itself. A nodal officer, a nodal ministry, someone from the trade in government, air charters between forts and wildlife centuries.

If there was one thing, if you were given a magic wand and you were asked change one thing, you have the power to change one thing immediately, what would that be?

Navin Berry: That’s a tough question, but let me try and answer it. Somewhere, I feel that we’ve been labouring over too many things for too long and they haven’t fructified and we are still struggling to say, let’s do this. For example, the National Tourism Board or a national committee or something. I mean these are very honestly in my very considered, very personal opinion, old hat. It’s all done and dusted now to have a tourism board after Mohammad Yunus committee recommended it almost 40 years ago. I mean it is not relevant anymore and we are still struggling to do those things. The other day I heard about Visit India Year. I mean Visit India Year has been tried, again and again, n ot by us but by many countries in the region. It is a thing of the past. So, let’s do something different. So, we are still struggling with ideas from the past

Secondly, I have written in my book that travel and tourism is going to prosper. Nobody is going to pull back travel and tourism. It is going to happen regardless of governments, regardless of anybody. There is that momentum in our economy, domestic tourism, domestic tourists, foreigners, they will keep coming. So, there is no threat to travel and tourism growing. But if you want to make a quantum difference to how tourism happens, then you’ll have to make a break from the past and look at new things to make the difference.

Barkha Dutt: What’s the one fundamental break from the past that you think we have to make?

Navin Berry: I think people haven’t understood the magic or the power of tourism and people still are struggling, in my opinion, still to think it’s elitist or we think it doesn’t matter. All the connotations that we have are all incorrect. The right one has not happened. That it is actually, tourism is the magic wand. Tourism can transform everything that’s happening in the country. And the greatest thing that is happening today in the world of tourism is experiential. Now experiential wraps up our hinterland. It captures the essence of India. So, if you want Bharat, that’s experiential. It’s not sitting in your Delhi, Bombay or Calcutta. So, you have that opportunity to actually cash upon is experiential. The thing is there, somebody has to put it together. And, it can make the difference.

Rajeev Sethi: Things can’t be just put on show. They are important to be able to create what is the magic of India. But I like the parts in your book where you very pragmatically state that unless these facilities are not enjoyed by the people themselves, what are we talking about? There has to be a certain level of integration. And if you utter the word ‘Paryatan’, it is not a word people understand in the villages of India. So, I think that point that it has to get more than just being tourists is important. So, the tourism wand has to reinvent its name, it has to become part something much bigger.

Barkha Dutt: Aman, you want to take that?

Aman Nath: I want to say that the book should also be read because it is the collective memory of tourism in India, post-independence, almost what not to do. Because if you read between the lines, you say, okay, they were fantastic people, some of whom are here, they tried their best, but because the mindset wasn’t changed and it still hasn’t changed because when you go to a village, I’ve just come from Benaras, it’s shocking to see how desperately our aspirations are to become western. In the news programmes, in conferences, wherever I went, all the girls have to wear red miniskirts. I mean, what has happened to the sari? So if you’re talking tourism, and we are still ashamed – in this morning in Benaras, one man was talking to me only in bad English. So, I told him, I am Indian, you can talk to me in Hindi. So, I said he was demonstrating superiority by talking English. So, the double standards I think in tourism have to go, all of us know, for example, the state in which the maximum alcohol is drunk. Do you know which one it is? Gujarat. Okay. And that is meant to be a dry state. So, who’s got the dots on the eyes and who are we fooling? So, we have to get it right.

Barkha Dutt: I think I want to pick up the last point of this homogenizing, Westernization, globalization, which is actually taking us away from our own sort of sub-cultures. Iqbal do you think that’s a problem?

Iqbal Chand Malhotra: I think everything has to go together. You cannot say that pass a judgement against malls or you can’t pass a judgement against some other kind of structure because the fact is that we need to create employment and tourism is a great means of creating employment. Our country in the last 20 years has suffered from too much competition from China and it has de-industrialized itself. Manufacturing has been badly wiped out. And without those jobs that manufacturing could have produced, if you have returned to the service sector, tourism is a great thing. And right from the micro level right up to the macro level, you need to really give it a big push. Now the question is that who are the minds who are going to get together and figure out an order of how we need to execute this and how we need to push this forward?

Barkha Dutt: Mr. Kant. We are having a robust conversation about how to sort of optimize India’s great potential in the tourism hospitality space. Can I request you to come in with your thoughts on the book and otherwise. And of course, there was a reference earlier to the whole Incredible India moment, but Navin was also making the argument that we need new ideas as we move ahead. So please.

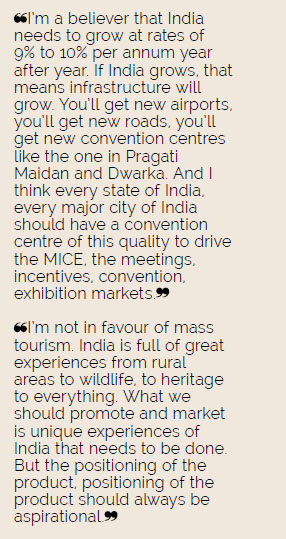

Amitabh Kant: So well, I’m a believer that India needs to grow at rates of 9% to 10% per annum year after year. If India grows, that means infrastructure will grow. You’ll get new airports, you’ll get new roads, you’ll get new convention centres like the one in Pragati Maidan and Dwarka. And I think every state of India, every major city of India should have a convention centre of this quality to drive the MICE, the meetings, incentives, convention, exhibition markets.

So, tourism is a subset of the Indian economy. You can never look at tourism in isolation. If India grows, India’s hard power grows. India soft power will automatically grow and India’s tourism will grow by leaps and bounds. Earlier you didn’t have airports, you didn’t have airlines, you didn’t have carriers which will bring in people, you didn’t have destinations. All that is dramatically changing and I think all that you need now is seven, eight state champions.

India’s got phenomenal tourism products, if you have about 10 states saying that I’m going to create jobs, tourism has to be seen from the perspective of the fact that while India is going to grow the sector, which is going to create jobs, is travel and tourism. It has the biggest multiplier impact. It’s multiplier impact across handloom, handicraft, craft and culture, all that is just phenomenal. For every job that you create in tourism, you create 10 other jobs and therefore we should not talk of tourism in isolation. We should just talk about the failure of tourism industry is that it has never said that it is the biggest job creator. India wants to grow with jobs. Tourism is the answer.

Barkha Dutt: Yes, actually I think you, Mr. Keswani, you made that point earlier. Aman, if you want, you want to react to that?

Aman Nath: Actually, the tourism minister, when you look at the hierarchy of ministers is somewhere down the line. For some reason. He’s like somebody who makes you laugh in a film, though he should be next to the finance minister and maybe above him because if France has a population of 70 million and can get 92 million tourists, imagine if you got 1.5 billion tourists. I mean the whole economy and the tourism minister would be handing out money to the finance minister.

So, we have to take ourselves much more seriously. You know, the valley of the noir in France gets more tourists than the whole of India. And that is just the size of Shekhawai, which is one seventh of Rajasthan. So, it is a matter of shame even I would say that with everything in place now, we have infrastructure in place also. When you go to the American airports, you think you’ve come to the third world.

Barkha Dutt: Navin, did you want to just add to your point about the political economy and I’ll give a last couple of comments to Mr. Kant, before we actually launch the book.

Amitabh Kant: No, no. I just wanted to respond to Aman’s point. I mean to my mind it’s not a correct analogy because tourism is essentially worldwide as regional in character. The challenge with India is that you’ve got Pakistan on one side, you’ve got Afghanistan on another side, you’ve got China on third side. So, the South Asia region is the least integrated region, so you don’t get regional tourists, otherwise you’ll have a billion plus people travelling to India. India is a long-haul destination. So, people who come to India prepare for coming here, but India gets tourists who have the longest stays here. So, my philosophy always has been that since India is so heavily overpopulated, we should focus on upmarket, high value tourists and not focus on numbers of people. The focus must be on unit value realization. If you get high value tourists, that’ll have a huge impact on India’s growth story.

Patu Keswani: See, the thing is that I have 10,000 employees in my company. 8,000 of them are class 10 graduated or less and 1000 of them, are disabled. We did this consciously. These are unemployable people. And let me tell you, across the spectrum of tourism this bunch, because India still has I think 20-30% not literate. Tourism needs functional literacy, not educational literacy. That’s the key. What we need is, like we said, a national leader like the Prime Minister himself with that level of political capital. And you need some competitiveness across states. One state proves it works. States are so competitive today that chief ministers go after a single silly project of $2 billion. The chief minister is running. Can you imagine somebody, a chief minister who transforms his state from the tourism perspective shows that it employs people who otherwise are potentially unemployable in this country, what it would do. So, to me, it’s simply a political economy decision. That’s my view. I mean, everything else will flow from that.

Rajeev Sethi: I’m just a little uncomfortable with economic indices as the one way to measure travel. And I want another word other than tourism. I think there’s much, much more to people going out, meeting, reaching out than high-end tourists who can pay big bucks for reviving our economy. I think there’s a huge amount to be said about creativity in the rural areas where there are people who want to meet people who want to have extended market. Whether that comes into the formal nomenclature of tourism as you, Amitabh are speaking of, I don’t know. I think these are things that we’ve been speaking about for about 60 years, but they still haven’t been able to see a coherent action on the field. So, you can call it tourism and you can say, okay, domestic tourism or rural tourism, but I think it is a little more than just tourism. I think there’s an ecosystem that creates, and it’s an ecosystem that I’m talking about. Tourism is one end of the spectrum, an important one. But I think we are talking about an ecosystem of appreciation, of conservation, of identity, of values and being just an experience. I think we have to retain something for ourselves.

Amitabh Kant: So Rajeev, I was talking from another perspective, and that is that mass tourism across the world has actually destroyed cultures. And I’ve seen this from very close quarters. It has led to huge unplanned unsustainable development. It has led to encroachments and therefore I’m not in favour of mass tourism. India is full of great experiences from rural areas to wildlife, to heritage to everything. What we should promote and market is unique experiences of India that needs to be done. But the positioning of the product, positioning of the product should always be aspirational. It should never be low value.

Barkha Dutt: Let me just ask you, before you came in, there was a suggestion from many of the speakers here about having someone who understands the trade in government. Do you think there’s merit in that?

Amitabh Kant: See, my belief really frankly, is that tourism ministry, I’m being very honest, that if India grows, if you’re able to create great infrastructure, if you have created 55,000 kilometres of road in the last seven, eight years, you’ve provided accessibility to all the destinations. If you built 30 new airports, you provided airports to all tier 2 and tier 3 cities now, which didn’t exist earlier. And if you’ve been able to really provide the last mile connectivity to the travel and tourism destinations, which has never existed in my time, and you’ve seen the emergence of 2 tier – clean sheets, clean beds, hotels, and resorts now, which never existed in my time. That means that tourism has come to stay. You don’t need a tourism ministry, according to me, honestly.

Barkha Dutt: So, who would take the decision?

Amitabh Kant: Why do you need decisions? You need tourism as a state subject. It should be driven by the states.

Barkha Dutt: Well, we had the exact opposite argument here where people are arguing for it to be a central subject.

Amitabh Kant: Absolutely not.

Barkha Dutt: Why not?

Amitabh Kant: Because Kerala has demonstrated that Kerala grew and became one of the greatest destinations of the world, has been ranked as one of the finest destinations of the world, with zero contribution from central government. Give the ownership to the states, make them responsible. What he’s saying, rank the states, name and shame them, without the states, you can’t deliver tourism.

Aman Nath: No, I think there’s room for both. Your high end is very good and you can also have the rest of India, otherwise they get isolated.