To begin with, the territorial dispute with the Dragon was not such a hostile affair. Aksai Chin, was considered by India as an uninhabitable high-altitude wasteland, of little use. Therefore, the need to send troops to occupy the frontiers was never felt. The other disputed area was South of the McMahon Line, in Arunachal Pradesh. The McMahon Line was part of the 1914 Simla Convention signed between British India and Tibet. China however, never recognised the agreement. China was testing the waters. While India was complacent and did not feel the need to assert its claims. China maintained a friendly posture, thereby succeeding in hiding its intensions. China annexed Tibet, but New Delhi continued to be as trusting as ever. During the 1950s, China started to construct a 1,200 km road connecting Xinjiang and Western Tibet, of which 179 km ran through Aksai Chin. India did not know about its existence until 1957. China had made its move and India was caught unawares. The Indian PM stated that Aksai Chin was “part of the Ladakh region of India for centuries.” On the other hand, Zhou Enlai said that their Western border had never been delineated and that Aksai Chin was already under Chinese jurisdiction. Clearly, India had missed the bus. Then 1962 happened and so much more, and India continued to miss the bus.

China has settled all boundary disputes with Myanmar, Nepal, North Korea, Mongolia, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Laos, Vietnam, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan. Only India and Bhutan border disputes remain to be resolved. Is this a mere coincidence? Or is there a message? Doesn’t China do everything in accordance with an agenda, a long-term plan?

Let us look at some of the border clashes that took place between India and China over the last many decades to draw some lessons from them.

Longju:1959. The first face-off between the two countries took place in Longju in Subansiri in Arunachal Pradesh on 25 August 1959. An Assam Rifles Post at this small village was attacked without provocation by the Chinese and the men were compelled to withdraw after suffering casualties. Soon after the Longju incident, the Indian Army took over operational control of the frontier in NEFA. Kongka:1959. The Ladakh Sector saw a more serious encounter a few weeks later when, on 20 October 1959. The Chinese ambushed a police patrol, killing nine and capturing another ten. The incident occurred South of the Kongka Pass, about 64-kilometres inside Indian territory. They returned the captured men but the shooting of the policemen brought a wave of anger throughout India. After the incident, the Western Sector was also handed over to the Army.

Dhola Post:1962. A border post set up by the Indian Army in June 1962, in the Namka Chu river valley. The area was to the south of the Thagla Ridge. On 20 September, the post was attacked by Chinese forces from the Thagla Ridge in the north, and sporadic fighting continued till 20 October when an all-out attack was launched by China leading to the Sino-Indian War. Facing an overwhelming force, the Indian Army evacuated the Dhola Post. The 1962 War is well documented and the Chinese attacks took place in both Arunachal Pradesh where their progress of operations threatened the plains of Assam and Ladakh, where the Battle of Rezang La has gone down in the annals of our military history for the bravery of the Company of 13 KUMAON which fought to the last man and last round.

Nathu La face-off 1967

Nathu La:1967. On 16 September 1965, during the Indo-Pak War of 1965, China issued an ultimatum to India to vacate the Nathu La Pass. However, GOC 17 Mountain Division, refused to do so. The conflict in 1967 at Nathu La began with minor altercations over small issues, such as new loudspeakers, a trench, a wire fence etc. These led to incidents of pushing, shoving, and punching between the soldiers. India felt that a fence might help stop daily arguments between soldiers. The Chinese, disagreed and several attempts were made to stop the fence. On 11 September, a tussle broke out and without any warning, the Chinese posts opened coordinated machine gun fire on Indian troops at around 0730 hours. Close to 70 casualties were reported in that first strike itself, as the Indian troops were exposed and unprepared.

The Indian Army under Major General Sagat Singh hit back with all they had and fought hand-to-hand battles around the pass. The duel continued for five days, after which the Chinese threw in the towel. The Indian Army taught the Chinese side a lesson and effectively occupied the dominating heights at Nathu La.

The Indian casualties in the action were over 200. The Chinese are estimated to have suffered about 300 casualties. This was the first time the myth of Chinese invincibility was broken.

Tulung La:1975. On 20 October 1975, once again Chinese forces crossed over into Indian territory, South of Tulung La, an uninhabited Pass in Eastern Arunachal Pradesh. The Chinese erected some stone walls on the Indian side of the pass. From these positions, the Chinese ambushed an Assam Rifles patrol, resulting in the death of four jawans. Their bodies were subsequently recovered by a patrol of 3/1 Gorkha Rifles.

Sumdrong Chu:1986. In 1986, Arunachal Pradesh was granted statehood. The Chinese government protested, as this was seen as a provocation by the Chinese. In 1986–87, a military stand-off took place between India and China in the Sumdorong Chu Valley bordering Tawang District. It was initiated by China moving troops to Wangdung, a pasture to the South of Sumdorong Chu which was Indian territory. On 14 June 1986, a patrol party of 12 ASSAM spotted a Chinese post and a few structures on the banks of the Sumdorong Chu. Indian troops occupied the ridges overlooking the Sumdorong Chu valley, including Langrola and Hathung La Ridge. The Indian Army then airlifted a Brigade from the 5 Mountain Division to Zemithang. Troop movement continued through early 1987 under a massive air-land exercise, titled Exercise Chequerboard, a high-altitude military exercise to test the military response in the North Eastern Himalayan region which served the purpose of demonstrating the might of the Indian Military to China.

The crisis was diffused after the visit of Indian External Affairs Minister Shri ND Tewari to Beijing in May 1987. The fallout from the standoff resulted in India and China restarting dialogue, which had been dormant since the 1962 war.

Depsang:2013. On 15 April 2013, approximately 50 Chinese troops intruded 19 km into India territory in the Depsang area and established a camp, at about 16,300 feet in the Raki Nala valley. The Indian Army immediately mobilised their own troops to contain the issue. The incursion included Chinese military helicopters entering Indian airspace to drop supplies to their troops. The 21-day face-off saw the two armies pitching tents and indulging in banner drills. The Indian Army showed deep resolve in handling the situation and stood their ground inspite of the adverse conditions. The fitness of the Indian troops was evident as they stood shoulder to shoulder day and night, while the Chinese could not bear the weather conditions. The tension was defused when both sides pulled back soldiers in early May.

Demchok:2014. In September 2014, India and China had another standoff, when Indian locals began constructing a canal in the border village of Demchok, Ladakh. The Chinese civilians protested with their army’s support. Indian Army deployed troops and urged the Chinese not to interfere inside Indian territory. The standoff ended after about three weeks, when both sides agreed to withdraw troops. Demchok had seen face-offs between Indian and Chinese troops earlier too. The Chinese often erect tents on the Indian side of the Charding Nala in Demchok. The tents are occupied by graziers who keep moving the tents westwards.

Chumar:2014. On 16 September 2014, a 16-day stand-off took place between Indian and Chinese troops in eastern Ladakh near the village of Chumar, after Indian soldiers blocked Chinese construction work inside Indian territory. The stand-off began after the PLA tried to extend the road from Chepzi towards Chumar. Soon, 1,500 Indian soldiers stood face-to-face with 750 PLA troops. The stand-off was resolved mutually between the two militaries.

Burtse:2015. In September 2015, Chinese and Indian troops faced off in the Burtse region in the Depsang Plains after the ITBP dismantled a watchtower the Chinese were building close to the mutually agreed patrolling line. The PLA called for reinforcements, and the Indian side too responded with additional deployments. The stand-off was resolved within a week by local commandrs at the ground level.

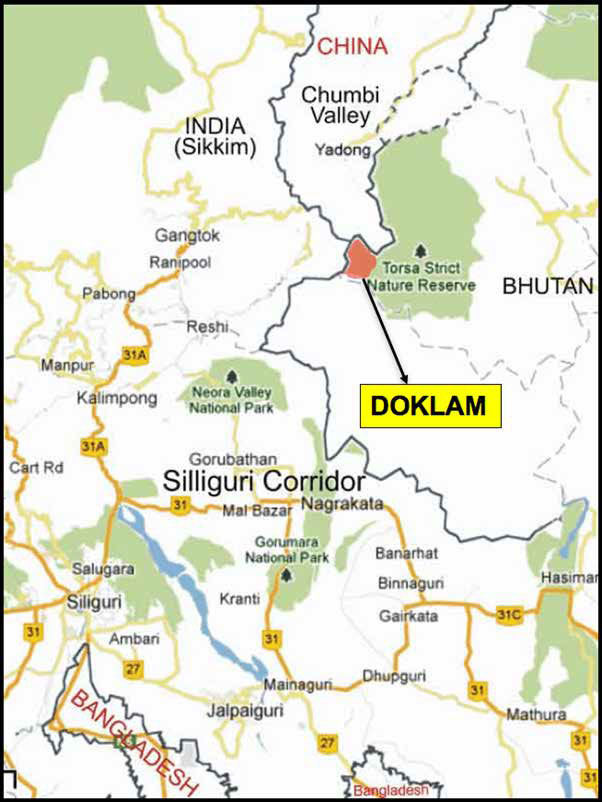

Doklam:2017. On 16 June 2017, the Chinese brought heavy road building equipment to the Doklam region in Bhutanese territory near the India-Bhutan-Tibet trijunction and began constructing a road in Bhutanese territory. The Indian soldiers blocked the Chinese from extending the road southward, the construction of which would have been strategically detrimental to India. The Indian Army warned the Chinese to go back and without waiting for a response the very next day immobilised their road construction equipment and physically blocked them. The Chinese were caught by surprise. The Chinese tried to get reinforcements but soon realised that they were outsmarted. Thereafter, the Chinese demanded that India should withdraw its troops first, but finally announced their withdrawal on 28 August, returning to their pre-16 June positions.

Doklam blokade: 2017

Galwan:2020. One of the most horrific and gruesome military encounters in modern times, fought with medieval age weapons, broke out between Indian and Chinese troops, at around 1900 hours on 15 June 2020, in the Galwan Valley in Eastern Ladakh. An Indian Army detachment of about 50 soldiers, led by Colonel Santosh Babu, Commanding Officer of 16 BIHAR, reached near Patrolling Point (PP) 14. The soldiers were unarmed, as part of the existing protocol. Their purpose was to confirm if the Chinese had indeed withdrawn from the location as per the de-escalation plan agreed upon between senior Indian Army and Chinese generals, on 6 June. However, the Indian detachment discovered that the Chinese were very much there. When the Chinese were confronted, they were adamant and refused to vacate their positions. It appeared that the Chinese were waiting for a chance to start a physical brawl and as it turned out were totally prepared for it. Pushing and shoving led to hand-to-hand fighting that continued for several hours right in pitch dark conditions. With reinforcements arriving the clashes spread out from the PP 14 area to a narrow ridge overlooking the river. The Chinese attacked Indian soldiers with iron rods and nail-studded clubs. The ferocity of the Indians surprised the Chinese who seemingly lost their numerical superiority and were on the back foot. Some soldiers, from both sides, fell into the river below. Colonel Santosh Babu and 19 Indian soldiers lost their lives that night. There were possibly 40-45 casualties on the Chinese side, as reported by the international media.

Galwan:2020. One of the most horrific and gruesome military encounters in modern times, fought with medieval age weapons, broke out between Indian and Chinese troops, at around 1900 hours on 15 June 2020, in the Galwan Valley in Eastern Ladakh. An Indian Army detachment of about 50 soldiers, led by Colonel Santosh Babu, Commanding Officer of 16 BIHAR, reached near Patrolling Point (PP) 14. The soldiers were unarmed, as part of the existing protocol. Their purpose was to confirm if the Chinese had indeed withdrawn from the location as per the de-escalation plan agreed upon between senior Indian Army and Chinese generals, on 6 June. However, the Indian detachment discovered that the Chinese were very much there. When the Chinese were confronted, they were adamant and refused to vacate their positions. It appeared that the Chinese were waiting for a chance to start a physical brawl and as it turned out were totally prepared for it. Pushing and shoving led to hand-to-hand fighting that continued for several hours right in pitch dark conditions. With reinforcements arriving the clashes spread out from the PP 14 area to a narrow ridge overlooking the river. The Chinese attacked Indian soldiers with iron rods and nail-studded clubs. The ferocity of the Indians surprised the Chinese who seemingly lost their numerical superiority and were on the back foot. Some soldiers, from both sides, fell into the river below. Colonel Santosh Babu and 19 Indian soldiers lost their lives that night. There were possibly 40-45 casualties on the Chinese side, as reported by the international media.

These were the first Indian casualties since the October 1975 incident of Tulung La and the first Chinese casualties after 1967 Nathu La.

Reading Between the Lines

The path to the Sino-Indian War of 1962 was littered with skirmishes and patrol clashes. The Longju/Kongka/Dhola incidents showed that India and China were on a collision course. The construction of a highway through Aksai Chin showed Chinese intent. The recent incidents follow a distinctive pattern too. There has been infrastructural enhancement in Tibet and Aksai Chin. Earlier the Chinese only set up camps. Now they are building field fortifications, logistic installations, helipads etc. All this needs to be noted. Smaller incidents of stare-downs between patrolling troops that sometimes become violent are rarely reported in the media. However, China does assess the Indian response.

Galwan was much more than just a border clash. It told the adversary that India will not accept nonsense. Galwan was a display of Indian resolve. The ramifications of Galwan were felt at the strategic level and this also changed the thinking about the Chinese threat amongst all like-minded countries.

Therefore, now what. What to believe and what not to. Obviously, the LAC does not hold any sanctity for the Chinese. There have been so many treatise/agreements between India and China. India-China Joint Working Group on the boundary question, 1988, Agreement on Maintenance of Peace and Tranquility, 1993, Agreement on Military Confidence Building Measures, 1996, Protocol for the Implementation of Military Confidence Building Measures, 2005, Agreement on the Political Parameters and Guiding Principles for the Settlement of the India-China Boundary Question,2005, Memorandum of Understanding, 2006, Establishment of a Working Mechanism for Consultation and Coordination on India-China Border Affairs, 2012, Border Defence Cooperation Agreement, 2013, to name a few. Have these agreements helped or did they serve only to push the problem under the carpet temporarily? Is China buying time through these agreements, while India is abiding by them.

All the incidents narrated above were instigated by China. India has not once crossed the line or attacked. India has never had any extra territorial designs. As they say “all is fair in love and war,” therefore, to ensure peace, India should do as China does.

Reading between the lines and following China’s past and present stance and activity, it is quite clear that all is not well. The Sino-Pak collusivity and China’s deep interest in PoK also needs consideration. Possibly Arunachal is the rouse and Ladakh is the objective. The nibbling westwards from Depsang to Demchok continues. Through this pastural diplomacy, our locals are losing their grazing grounds, as it has often been reported. China’s so-called package offer of 1960, which had been alive until recently highlighted China’s aim. Accept status quo in the Eastern Sector generally conforming to the McMahon Line, except Tawang, which was possibly kept as a bargaining chip. In return India concedes Aksai Chin to China in the Western Sector.

Today’s India is wise to take note and be wary of the unworthy.

Conclusion

The India China War of 1962 erupted due to the different perceptions of the border. This issue has defied any solution for the past six decades primarily because China uses this as a pressure point to keep India unbalanced. Till date, every now and then China does mention the “different perceptions.” China wants to occupy every high ground on the LAC. It uses the “different perception” card to achieve that.

To sum up relations have been bhai-bhai, bye -bye and buy-buy before the deterioration that has taken place lately due to China’s aggressiveness and expansionist policies.

While there is no doubt that both India and China need to rebuild trust but they cannot agree on the process. China has been challenging India’s multilateral aspirations and wants to reduce India’s capacity to manage the consequences of China’s rise in the region. The war in Ukraine has added another dimension as Russia, traditionally on India’s side in multilateral regional arrangements, seems neutralised by its proximity to China.

The escalating tensions and aggression of China since 2013 is therefore no coincidence. Their coercion on the border and naval build-up in the Indian Ocean, force India into a costly arms race and therefore is pushing it closer to the US which is disliked by China. In the ongoing great power competition between China and the US, every issue becomes a zero-sum game. This makes it harder for India to solve its border conflict with China and at the same time manage China’s rise and growing assertiveness in the Indo-Pacific region in a peaceful manner.

The possibilities of the re-emergence of conflict, even in the locations where tensions have apparently eased up remain high. In a scenario where China continues its aggressive measures against India, in the military realm, coupled with the differing world views of the two, the possibility of cooperation has reduced if not disappeared. It is therefore imperative for India to contest all Chinese actions strongly and work at reducing the power differential that exists between the two countries.

War does not suddenly arrive. It charts a course that is visible to those who wish to see it. If the signs are read correctly, then war does not come. If signs are ignored, as they were prior to 1962, then an unwanted visitor enters uninvited.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Maj Gen VK Singh, VSM was commissioned into The Scinde Horse in Dec 1983. The officer has commanded an Independent Recce Sqn in the desert sector, and has the distinction of being the first Armoured Corps Officer to command an Assam Rifles Battalion in Counter Insurgency Operations in Manipur and Nagaland, as well as the first General Cadre Officer to command a Strategic Forces Brigade. He then commanded 12 Infantry Division (RAPID) in Western Sector. The General is a fourth generation army officer.

Maj Gen VK Singh, VSM was commissioned into The Scinde Horse in Dec 1983. The officer has commanded an Independent Recce Sqn in the desert sector, and has the distinction of being the first Armoured Corps Officer to command an Assam Rifles Battalion in Counter Insurgency Operations in Manipur and Nagaland, as well as the first General Cadre Officer to command a Strategic Forces Brigade. He then commanded 12 Infantry Division (RAPID) in Western Sector. The General is a fourth generation army officer.

Major General Jagatbir Singh was commissioned into 18 Cavalry in December 1981. During his 38 years of service in the Army he has held various command, staff and instructional appointments and served in varied terrains in the country. He has served in a United Nations Peace Keeping Mission as a Military Observer in Iraq and Kuwait. He has been an instructor to Indian Military Academy and the Defence Services Staff College, Wellington. He is a prolific writer in defence & national security and adept at public speaking.

Major General Jagatbir Singh was commissioned into 18 Cavalry in December 1981. During his 38 years of service in the Army he has held various command, staff and instructional appointments and served in varied terrains in the country. He has served in a United Nations Peace Keeping Mission as a Military Observer in Iraq and Kuwait. He has been an instructor to Indian Military Academy and the Defence Services Staff College, Wellington. He is a prolific writer in defence & national security and adept at public speaking.