Our National Monuments List Needs to be Reviewed, Rationalized towards Better Management, says Sanjeev Sanyal

A recent report put out by Economic Advisory Council to the PM, authored by Sanjeev Sanyal, Member, along with Jayasimha K R and Apurv Kumar Mishra, has suggested far reaching changes to the current manner of declaring monuments of national importance. It is a monumental work in itself, an important first steps towards taking a significant second look at how we manage our national resources in this sector.

Speaking to Destination India, Sanyal said it was critical to take these first steps. Asked what next, he said the list of less important monuments, or those of local relevance, could be handed over to the state governments. He saw a bigger role for INTACH like bodies that could work more closely with state governments.

Asked if this list would see additions as well, he said certainly this must and would happen. Too often, we have missed out on what are really old monuments and which merit much greater attention. He saw the role of private sector increasing in this area, and possibly greater collaboration between the two – private and governments, both at the centre and in the states.

Here is the selective summary of the report:

India currently has 3695 ‘Monuments of National Importance’ (MNI) that are under the protection of Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). The Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act (AMASR Act), 1958 (amended in 2010) provides for the declaration and conservation of ancient and historical monuments and archaeological sites and remains of national importance. Occasionally there are debates about the nature and scope of preservation and protection of these monuments, allocation of funds, quality of expenditure, quality of visitor amenities at the monuments, unclear roles and responsibilities of the National Monuments Authority (NMA) and so on.

However, there has been almost no discussion about the existing list of monuments of national importance and how a monument or a site is so declared. The list has also been kept outside the ambit of any review due to which it has become unwieldy. Scores of minor and insignificant monuments have been declared as MNI. Therefore, the current list requires immediate attention for drastic rationalisation.

Once a monument or a site is declared to be of national importance, they come under the supervision of ASI which functions under the provisions of the AMASR Act, 1958. Onehundred-meter radius of the monument is then considered a ‘prohibited area’ where there is a ban on construction activities. Further 200 meters (i.e. 100+200 meters) is considered a ‘regulated area’ where there are regulations on construction.

There are several problems plaguing the current list of MNI. This report examines three major problem areas. The report also analyses sources of these problems and provides actionable policy prescriptions/recommendations.

Three major problem areas with the current list of monuments of national importance are:

1. Selection Errors: a. Minor monuments considered as monuments of national importance b. Movable antiquities treated as monuments of national importance c. Untraceable monuments still being considered as monuments of national importance

2. Geographically Skewed Distribution of Monuments

3. Inadequate and Geographically Skewed Expenditure on Upkeep of Monuments

1. Selection Errors One of the major problems with the current list relates to the errors in the selection of monuments. A large number of MNI seem not to have national importance or historical or cultural significance. Our analysis estimates that around a quarter of the current list of 3695 MNI may not have ‘national importance’ per se.

1. Selection Errors One of the major problems with the current list relates to the errors in the selection of monuments. A large number of MNI seem not to have national importance or historical or cultural significance. Our analysis estimates that around a quarter of the current list of 3695 MNI may not have ‘national importance’ per se.

The three significant selection errors are: (a) minor monuments as monuments of national importance; (b) movable antiquities considered as monuments of national importance; (c) untraceable monuments still being considered as monuments of national importance.

2. (a) Minor monuments as monuments of national importance in the current list there are an inordinate number of minor monuments that have been declared as monuments of national importance.

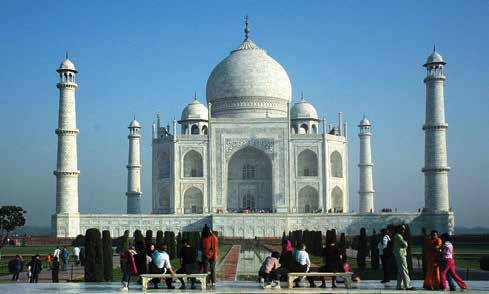

For instance, around 75 graves/cemeteries of British officers and soldiers of neither architectural significance nor historical or cultural importance. For example, a grave erected in the memory of Lieutenant H. Forbes in Suchima in Kohima district, Nagaland. Lieutenant Forbes was a British officer who died after being mortally injured during an assault with the Naga villagers at Suchima in 1879. The memorial structure has no architectural significance or cultural value and the individual was of no historical consequence. Yet, this structure gets the same level of protection as our most cherished monuments like Ellora Caves or Taj Mahal or group of monuments at Hampi!

The list also includes around 109 ‘Kos Minars’ – plain-looking brick or lime mortar columns that acted as milestones on Mughal highways – which have been declared as monuments of national importance. Although there is a need for protecting Kos Minars, it is unclear why they should be treated as national monuments.

(b) Movable antiquities treated as monuments of national importance The list includes several moveable, standalone ‘antiquities’ like pieces of sculpture, statues, cannons etc. which are being treated as ‘monuments’. An example of a standalone antiquity considered as a monument is the small statue of a tiger belonging to the 17th century near Kumta in Uttara Kannada district of Karnataka. The statue is about one metre in length, 50 cm in width and 40 cm in thickness. Not only is it difficult to provide protection to an isolated standalone antiquity located in the open, the imposition -of ‘prohibited’ area and ‘regulated’ area rules around national monuments often causes complications and logistical problems for development activities. Antiquities should not be included in the MNI list.

(c) Untraceable monuments still being considered as monuments of national importance Finally, apart from minor monuments and antiquities being considered MNI, monuments which are not traceable are still included in the list of MNI.

Comptroller and Auditor General’s (CAG) Performance Audit of Preservation and Conservation of Monuments and Antiquities (2013)1 reported that 92 monuments and sites that were declared as monuments of national importance were untraceable. This was the outcome of a physical inspection carried out by CAG along with the ASI for the purpose of the performance audit. It is important to note that out of 3695 MNI, only 1655 were physically inspected. Therefore, it is likely that the actual number of missing monuments is higher than the number reported. Some examples of untraceable monuments include: Kos Minar 13 in Mujessar in Haryana; the remains of a copper temple in Lohit, Arunachal Pradesh.

Comptroller and Auditor General’s (CAG) Performance Audit of Preservation and Conservation of Monuments and Antiquities (2013)1 reported that 92 monuments and sites that were declared as monuments of national importance were untraceable. This was the outcome of a physical inspection carried out by CAG along with the ASI for the purpose of the performance audit. It is important to note that out of 3695 MNI, only 1655 were physically inspected. Therefore, it is likely that the actual number of missing monuments is higher than the number reported. Some examples of untraceable monuments include: Kos Minar 13 in Mujessar in Haryana; the remains of a copper temple in Lohit, Arunachal Pradesh.

1. Comptroller and Auditor General of India. Performance Audit of Preservation and Conservation of Monuments and Antiquities, Report No.18 of 2013 (Performance Audit).

Later ASI traced/identified 42 monuments that physically existed, 14 affected due to urbanization and 12 submerged under reservoirs dams. The remaining 24 monuments and sites still remain untraceable. Despite many monuments and sites being untraceable for decades now, they still continue to be included in the list of MNI. While the above examples are of monuments that are not traceable, there is a case of a statue that was exported but is still being treated as a monument of national importance. The statue of John Nicolson, a British brigadier, that once stood in front of Kashmiri Gate in Delhi was shipped to Northern Ireland in 1958. Despite being exported to another country over six decades ago, the statue still continues to be in the list of monuments of national importance!

2. Geographically Skewed Distribution of Monuments – Though monuments of national importance are spread across the country, there is an imbalance in their geographical distribution. Over 60% (2238 out of 3695) of them are located in just five states: Uttar Pradesh, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra. By way of illustration, while the city of Delhi alone has 173 MNIs, a large state like Telangana has only eight. Culturally and historically significant states like Bihar (70), Odisha (80), Chhattisgarh (46) and Kerala (29) have disproportionately fewer MNI.

While it is understandable that a historically important city like Delhi will have a cluster of sites, large forts and palaces count as one site. Therefore, the monuments list from Delhi contains dozens of minor monuments, including obscure tombs, declared as MNI. An example of this is Chhoti Gumti in Green Park area which is a small domed building that houses an unknown grave said to be of the Lodhi period.

3. Inadequate and Geographically Skewed Expenditure on Upkeep of Monuments India’s expenditure on monuments of national importance is woefully little and inadequate. Even the little amount spent needs to be better utilised for proper upkeep of monuments. A significant proportion of the allocated amount is spent on peripheral activities and annual maintenance. In 2019-20 the budgetary allocation for “conservation, preservation and environmental development” of 3695 MNI was only INR 428 crores. This works out to a paltry sum of INR 11 lakhs

per MNI.

Compounding the problem of inadequate allocation and expenditure is the issue of imbalance in geographical distribution of funds for the protection of monuments. Of the INR 428 crores allocated in 2019-20, the city of Delhi with 173 monuments was allotted INR 18.5 crores, while Uttar Pradesh with 745 monuments was allotted just INR 15.95. Maharashtra with 286 monuments was only allotted INR 20.98 crores. The fiscal imbalance is aggravated because the revenue collected at monuments through various sources like ticketing, photography, filming, etc. (at selected monuments of national importance) is not utilized either by the Ministry of Culture or by the ASI. The revenue amount is deposited in the Consolidated Fund of India.

Compounding the problem of inadequate allocation and expenditure is the issue of imbalance in geographical distribution of funds for the protection of monuments. Of the INR 428 crores allocated in 2019-20, the city of Delhi with 173 monuments was allotted INR 18.5 crores, while Uttar Pradesh with 745 monuments was allotted just INR 15.95. Maharashtra with 286 monuments was only allotted INR 20.98 crores. The fiscal imbalance is aggravated because the revenue collected at monuments through various sources like ticketing, photography, filming, etc. (at selected monuments of national importance) is not utilized either by the Ministry of Culture or by the ASI. The revenue amount is deposited in the Consolidated Fund of India.

Even as the budgetary allocation for the upkeep 4 and conservation of monuments has been historically low, the government has not come up with other sustainable revenue generation models over the last several decades.

There is another issue related to information available on monuments at their locations. A large number of monuments do not have notice boards that provide basic information about the historical, cultural or architectural significance of the monuments and why they are considered monuments of national importance. Sources of the Problems One of the major sources of the problem plaguing the identification and preservation of monuments of national importance lies in the AMASR Act, 1958 itself. Neither the Act nor the National Policy for Conservation (2014) have defined what the term ‘national importance’ means. The Act also does not have a substantive process/criteria prescribed for identifying a monument as a monument of national importance. In absence of well-defined principles, the selection of monuments of national importance seems to be arbitrary.

ASI has a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) which entails filling of Form B and formation of a Technical Evaluation Committee. These requirements are at best a procedural formality. Out of the current 3695 monuments of national importance, 2584 of them got shifted en masse from the colonial-era list. Between 1947 and the passing of the AMASR Act 1958, another 736 monuments were added to the list, of these over 444 were from the princely states. The 1958 Act then declared all of them to be of national importance without reviewing/scrutinising the list.

Moreover, there is no comprehensive database of all the 3695 MNI available with the ASI which has information on their provenance, including historical importance, geographical description, cultural and architectural significance. Also, the list has largely been kept outside the ambit of any kind of review or scrutiny. The amendment to AMASR Act, 1958 in 2010 established the National Monuments Authority (NMA). The Act then mandated NMA to prepare bye-laws for all the 3695 monuments.

However, in the past 11 years, NMA has framed bye-laws for only 126 MNI, most of which are awaiting the nod of ASI.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Sanjeev Sanyal is a member of Prime Minister’s Economic Advisory Council. He has worked on several editions of the Economic Survey of the Ministry of Finance. He has authored several books, including ‘Revolutionaries’, that was recently released by Home Minister Amit Shah.

Sanjeev Sanyal is a member of Prime Minister’s Economic Advisory Council. He has worked on several editions of the Economic Survey of the Ministry of Finance. He has authored several books, including ‘Revolutionaries’, that was recently released by Home Minister Amit Shah.

Recommendations

- ASI should come up with substantive criteria and a detailed procedure for declaring monuments to be of national importance. AMASR Act, 1958 may be amended to define parameters like national importance and elucidate what constitutes architectural, historical and cultural significance. However, it may be simpler to do it through an executive order.

- ASI should publish a book of notifications with detailed information about the provenance of monuments of national importance.

- Monuments with local importance should be handed over to the respective states for their protection and upkeep. All the states should be encouraged to have their own 5 specialised institutions for the protection of monuments, archaeology research and excavations. This will help facilitate the transfer of monuments with local importance to states.

- Standalone antiquities should be removed from the list of monuments of national importance. Wherever possible, they may be shifted to museums for better upkeep.

- Untraceable and minor monuments should be denotified at the earliest.

- An effort should be made to restore geographical balance in the list of MNI and new monuments should be added to this list based on well-defined criteria and procedures.

- Allocation of funds for the protection of monuments of national importance should be increased. At the same time, revenue streams such as tickets, events, fees and other sources should be leveraged more proactively and the proceeds should be retained by ASI.

- Separation of responsibilities between ASI (maintenance of monuments) and NMA (development of surrounding area) seems to not have worked. It is advisable to merge these responsibilities and give them to NMA. The main ASI should focus only on archaeology research, excavation, restorations and maintenance of museums. NMA can function as an autonomous body under ASI.

- Most of the above recommendations can be implemented through executive orders and do not need changes in the AMASR Act, 1958.