The Election Commission of India has for long been the shining symbol of democracy all over the world. To further solidify this reputation, we must ensure that all the safeguards are in place that increase and institutionalize the credibility and autonomy of EC. With the 2024 general elections coming up in the near horizon, and elections in five states this year, it is all the more urgent and must be one of our great priorities.

In the light of serious concerns concerning the electoral process in recent times, last week, many prominent personalities signed a public petition addressed to the CEC urging the ECI to implement its constitutional mandate to conduct free and fair elections. They highlighted many issues ranging from EVM/VVPAT system and electoral rolls to money power in elections.

What, then, must be done to sustain and strengthen the constitutional ideals in the current moment? I propose that we carry out reforms classified under four broad “categories”: (I) reforms to strengthen and revitalize the Election Commission; (II) reforms to fundamentally alter the electoral system itself (III) reforms to increase and institutionalize transparency; (IV) and finally reforms for cleansing politics at large.

Reforms to EC: Appointments and Registrations

The first important measure to ensure non-partisanship and impartiality of the EC would be through the appointment of the members of the Election Commission through a collegium, as is also recommended in the 255th report of Law Commission of India.

On the day before the conclusion of the Monsoon Session, the government presented the Chief Election Commissioner and other Election Commissioners (Appointments, Conditions of Service, Term of Office) Bill in the Rajya Sabha. This follows the significant March verdict of the Supreme Court regarding the appointment procedure for polling officials. The Selection Committee now would consist of the PM as the chair person, the union cabinet minister nominated by the PM and the Leader of the opposition.

However, this does not reduce the hold of the executive over appointments as instead of the government unilaterally making appointments, a govt dominated collegium is now proposed. I suggest that the collegium system will be credible only if unanimity is added as a precondition.

Additionally, the EC’s reputation also suffers when it is unable to tame recalcitrant political parties, including the ruling party, at the state level or at the centre. This is because despite being the registering authority under Section 29A of the Representation of the People Act, 1951, it has no power to de-register them even for the gravest of violations. This is a debilitating concern given that it erodes the EC’s authority in upholding electoral sanctity, and must therefore be a priority reform.

The most important element in EC’s credibility, however, is the way how the incumbents conduct themselves. Total even handedness, non-negotiable neutrality and absolute level playing field for all parties and candidates are imperative. It’s a pity that it came into question recently. The entire edifice of credible elections is built on the image of the commission. We cannot afford any dilution of this image.

Reforms to the Electoral System: FPTP vs PR and Single Phase

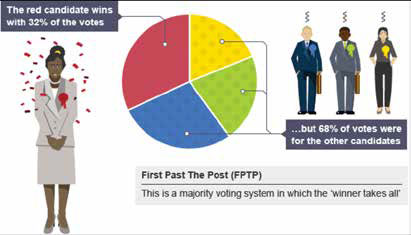

Currently, we follow the Westminster model, employing the first-past-the-post (FPTP) system. Voters elect representatives to the Lok Sabha, with candidates securing the highest number of votes in their constituencies declared winners. Despite its efficiency, FPTP has shown flaws, as illustrated in the 2014 general elections, where the Bahujan Samaj Party secured 20% of the national vote share in UP but no seats.

Proportional representation (PR) could be an alternative, allocating seats to parties in proportion to their vote share. However, PR has issues too, like making government formation challenging due to fragmented votes, often requiring coalitions. The list system within PR can prioritize party-favored candidates over voter-preferred ones, potentially leading to undue influence on elected representatives.

A hybrid solution, akin to Germany, Sri Lanka and Nepal’s models, could combine FPTP and PR benefits. In India, this would necessitate enlarging the Lok Sabha or reducing constituencies. Given India’s constituency-voter ratio, increasing Lok Sabha seats seems more feasible, now possible in the newly constructed building. A concern is model code violations in multi-phase elections, when leaders campaign during silent periods despite restrictions. The Election Commission’s efforts, like vulnerability mapping and central armed police personnel deployment, have addressed this, suggesting that peaceful single-phase elections are possible.

A hybrid solution, akin to Germany, Sri Lanka and Nepal’s models, could combine FPTP and PR benefits. In India, this would necessitate enlarging the Lok Sabha or reducing constituencies. Given India’s constituency-voter ratio, increasing Lok Sabha seats seems more feasible, now possible in the newly constructed building. A concern is model code violations in multi-phase elections, when leaders campaign during silent periods despite restrictions. The Election Commission’s efforts, like vulnerability mapping and central armed police personnel deployment, have addressed this, suggesting that peaceful single-phase elections are possible.

Transitioning to single-phase elections could streamline the process, shortening the election cycle to 30-35 days from the current 2-3 months. This curtails communal tensions, caste dynamics, and misuse of money power during extended campaigns. Furthermore, this change could reduce violations of opinion and exit poll restrictions.

The final point worth mentioning here concerns the EVM/VVPAT debate that keeps rising up ever so often. The Election Commission challenged conspiracy theorists multiple times to prove EVM hacking, yet no party accepted. In 2010, after an all-party meeting, the adoption of VVPATs was unanimously recommended and accepted. Two EVM factories developed VVPATs under the monitoring of a committee from five IITs. Rigorous trials and simulations were conducted in 2011-12 across diverse Indian cities before deploying VVPATs in 20,000 booths, gradually expanding to all. The Supreme Court praised these efforts in 2013, directing funds for VVPATs in all booths by 2019. Since 2017, all elections included VVPAT-attached EVMs. Despite counting 1,500 machines, no mismatches occurred.

Reforms for Transparency: Electoral Financing and Inner-Party Democracy

Regarding the question of expenditure on campaigns, and more broadly of controlling money power in elections, the EC must be given an open and active role in regulating what politicians and political parties spend while conducting campaigns. The Electoral Bonds Scheme announced in 2018 only exacerbates the opacity, unaccountability and dependency on illicit and anonymous sources of electoral financing, including foreign sources.

Regarding the question of expenditure on campaigns, and more broadly of controlling money power in elections, the EC must be given an open and active role in regulating what politicians and political parties spend while conducting campaigns. The Electoral Bonds Scheme announced in 2018 only exacerbates the opacity, unaccountability and dependency on illicit and anonymous sources of electoral financing, including foreign sources.

Instead, as EC has repeatedly recommended, it would serve transparency better if the accounts of the party finances are to be audited by a list of chartered accountants recommended by the EC or CAG. The results of this audit are to be made available to the public on the EC’s website, along with the website of the political party concerned. If implemented, this would go a long way in strengthening EC’s ability to curb corruption and black money in electoral politics.

An important alternative is to do away with private fund collection altogether and replace it with public funding of political parties. A National Election Fund could be set up to which all donations could be directed. The Fund could then be allocated to political parties on the basis of their electoral performance.

Likewise, an important element of electoral democracy pertains to the management and conduct of political parties. Thus, the functioning and regulation of parties, from their provenance to their electoral campaigning must be closely scrutinized for the betterment of the democratic process.

In 1996, the Commission had issued a review of intra-party elections across the country, and the results were disappointing. Thus, provisions must be made to introduce inner-party democracy within the political parties. This should include mandatory secret ballot voting for all elections for all inner-party posts and selection of candidates by the registered members, as suggested by Law Commission Reforms and practised in Germany. Furthermore, this whole process of party elections must be overseen by an observer appointed by the Election Commission of India.

Reforms for Cleansing Politics: Decriminalization, Financing, and Media

The criminalization of politics has been a constant threat to the proper functioning of democracy in India. According to the association of Democratic Reforms, nearly half of the 17th Lok Sabha members have criminal charges against them. Of the 543 elected Lok Sabha members

233 have criminal charges, of which 29 per cent of elected members have criminal cases of rape, murder, attempt to murder and crime against women.

What then is the way out? There are three possible options. One, the election law (Section 8 of the Representation of the People Act, 1951) which disqualifies a person convicted with a sentence of two years or more from contesting elections, should be amended to debar charge sheeted or under-trial persons from contesting elections. Two, political parties should refuse tickets to the tainted. Three, fast-track courts should decide the cases of tainted legislators quickly.

What then is the way out? There are three possible options. One, the election law (Section 8 of the Representation of the People Act, 1951) which disqualifies a person convicted with a sentence of two years or more from contesting elections, should be amended to debar charge sheeted or under-trial persons from contesting elections. Two, political parties should refuse tickets to the tainted. Three, fast-track courts should decide the cases of tainted legislators quickly.

While electoral financing and criminalization affect the institutional performance and vitality most significantly, there are also matters that have a broad-based impact on the cultural and social facets of democracy, in other words, the nation’s civil society, including its media.

In the recent years, hate speech in all its varieties, has acquired a systemic presence in the media and the internet, from electoral campaigns to everyday life. Abusive speech directed against minority communities, particularly Muslims, and disinformation campaigns on media networks have made trolling and fake news significant aspects of public discourse. The ethical and moral bonds of our democracy are taking a hit.

In the recent years, hate speech in all its varieties, has acquired a systemic presence in the media and the internet, from electoral campaigns to everyday life. Abusive speech directed against minority communities, particularly Muslims, and disinformation campaigns on media networks have made trolling and fake news significant aspects of public discourse. The ethical and moral bonds of our democracy are taking a hit.

In fact, the Indian Penal Code, as per the Sections 153, 295A and 298, criminalizes the promotion of enmity between different groups of people on grounds of religion and language, alongside acts that are prejudicial to maintaining communal harmony. Whereas Section 125 of Representation of People Act deems that any person in connection with the election promoting feelings of enmity and hatred on grounds of religion and caste etc is punishable with imprisonment extendable up to three years and fine or both. Section 505 criminalizes multiple kinds of speech such as those that cause public disorder.

However, it is important to highlight that while there maybe constitutional and electoral provisions, sufficient or otherwise, to treat the phenomenon of hate speech legally and institutionally, what we need to solve the problem at its roots is political will, morality and reverence for the secularism and multicultural tolerance.

Another urgent recommendation concerning the role of media, which had first been sent to the PM in 2004 and then reiterated in 2013 by the EC, was to prohibit the dubious opinion polls during elections. There was also a proposal tabled by the EC in 2004 and again in 2015 suggesting that government-sponsored advertisements be prohibited sta‑rting from 6 months before the elections. With elections becoming increasingly mediatized infected with reigning fake news and paid news, it is indispensable to the functioning of democracy that media be independently regulated so as to ensure proper electoral integrity.

Conclusion

Electoral reforms must be undertaken not to serve narrow political dividends but to enhance and strengthen our institutions and the structures of democracy.

In order therefore to achieve a greater democracy, with an independent EC, we must commit ourselves to prioritising the necessary reforms that make it possible.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

S Y Querishi is a former Chief Election Commissioner; former Civil Servant from Haryana cadre of IAS.