We are all familiar with the sweeping scale of Indian heritage and culture, and its cumulative impact on projecting the nation’s soft power, a crucial component for travel and tourism. But soft power is intrinsically linked to hard power, argues Amish Tripathi – a renowned writer turned diplomat, whose books have offered ground-breaking perspectives on Indian history and mythology. It is no coincidence, therefore, that India’s unprecedented clout in global affairs in the first century coincided with the nation accounting for 30-35 per cent of the world’s GDP, he says!

INTACH recently organised a webinar titled ‘Exploring India’s Ancient Heritage,’ anchored by Nishant Singh, Director, INATCH, where Amish delivered a masterclass on the subject, outlining why our heritage and history had not yet been adequately researched. He spoke on contentious topics such as the Aryan vs Dravidian theory, the left vs right debate on matters of heritage and history, and the Delhi-centric historical perspective of Indian scholars.

Here are some excerpts from the discussion:

Decoding soft power

“A necessary but not sufficient condition for soft power is hard power. If you don’t have a big economy, you will not have hard power. But if you have hard power, it doesn’t automatically mean you will get soft power. The USA has both,” explains Amish, speaking from his London office as he weighs in on how India could leverage its soft power better. Several Southeast Asian nations changed their entire societal structures and Indianised themselves, taking on Hindu names and building Hindu-style temples, he explained. But that ancient pivot towards India was built on “a lot of hard power,” he said, adding that India was the most prosperous nation in the world.

He offered a simple yet intriguing explanation on why India continued to enjoy substantial gold reserves despite having no mines such as in Australia or California in the United States. India’s gold reserves were an outcome of centuries of trade surpluses, he informed.

Ayurveda, Yoga, Mahatma Gandhi, Gautam Buddha, were all associated with India and seen positively, he said, noting that the Indian diaspora had contributed to building ‘Brand India’ in equal measure. “Educationally and economically, Indians tend to do quite well. So, we are seen as good additions. Ayurveda, I think, can be a massive source of positive soft power. It is part of our heritage. We have not researched it enough,” he believed.

The Aryan vs Dravidian theory: A well-concocted lie

The Aryan invasion theory was the great piece of fiction written by the British since the ethereal plays of Shakespeare, said Amish. He suggested that there was no archaeological evidence to support an evasion. “Let there be shastrathas (debates) like in ancient India between the proponents of both the theories. I would love to see such debates,” he said.

Civilisational continuity is India’s most significant differentiator

India was the only nation in the world that was a “living pre-Bronze age culture,” he said. People across the globe could connect with the truly ancient past, Amish argued. He said that India being the only pre-Bronze age pagan culture still alive, was a fantastic story. “Every other pre-Bronze age culture has been wiped out, often not being that they died out naturally but because invaders attacked them,” he explained. Amish spoke about the mighty Zorastrian Persian empire, arguably one of the greatest civilisations in the ancient world, whose culture now survived in reminiscence in India. That the Indian society had greatly respected its folk traditions was one of the most critical factors for the survival of Indian culture, he believed. “We are not weaklings; we are the toughest buggers. We are around despite horrific invasions,” he insisted.

The left vs right debate is an imported construct: Indians are mostly centrists

The leftists and the rightists were “a match made in heaven,” said Amish, noting that both the factions needed one another to showcase the other as an extreme entity. He believed that an adversarial approach was one of the worst western imports to India. Indian debating traditions were quite different where one listened with an open mind and “the structure of the debate led to light and not heat.” He advocated surrendering and doing away with the left-right construct, which essentially manifested after the French revolution and was an inherently foreign construct. “We Indians are largely centrists,” he said.

Tracing the historical roots to mythological constructs

Indians believed that absolute truth was only possible in mathematics and mythology was akin to being an adult who believed in his version of the truth, suggested Amish. He noted that multiple and expansive research on the geographical descriptions in mythological texts, mentioning Sri Lanka and even Central Asia, were historically accurate. The software was now available to reconstruct the exact nakshatra (stars) mentioned in the ancient texts such as Ramayana and Mahabharatha. Still, it had not been studied in detail for various reasons. “We are a poor country and money would go to other issues. There were also biases among our scholars,” he said. Amish favoured conducting more studies to understand them better.

A Delhi-centric historical perspective has offered an incomplete picture of the past

Amish suggested that much of India’s historical constructs were shaped by the British and Indians, unfortunately, have carried on with the same narrative for the past 70 years. “The history taught to us is more about our invaders and not about our ancestors who fought them,” he said. While the Maurya and Gupta empires were too massive to be ignored, several powerful empires across the country had not been focussed upon, he said, adding that the Pratiharas, Cholas and the Sikh dynasty, among others, were not discussed at length. “Bijapur was wealthier and bigger than any Mughal city in its time,” he said. He believed that “excessive Delhi-centricity” had led to ignoring of Indian history.

Our take

We have always propounded that India’s heritage and culture are its most robust pegs to project its soft power. Diverse Indian art and architecture, and dances and folk traditions, among others, are perhaps unmatched. And we say it responsibly. That we have not adequately capitalised on them is also a fact and requires no debate.

We have had many pressing concerns, as a young nation in our past 70-odd years, with health, poverty alleviation and fixing our fundamental challenges of roti, kapda and makaan taking precedence over matters of heritage and culture.

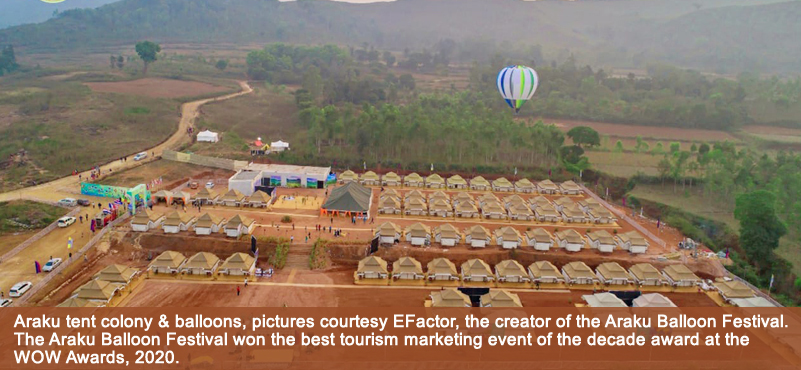

Could tourism and travel provide the necessary impetus to study, conserve and protect our heritage and history better? India’s heritage, such as monuments, must become self-sustainable to provide the finances needed to undertake such studies and projects to bring about a discernible change. Tourism and travel are the most enabling tools at the nation’s disposal. They can create a new-found interest among the masses, drive conversations and create the requisite traction to bring focus on our neglected and less-studied past. How we utilise them will decide the pace and quantum of our desired change.